What is the ACL & What Does it Do?

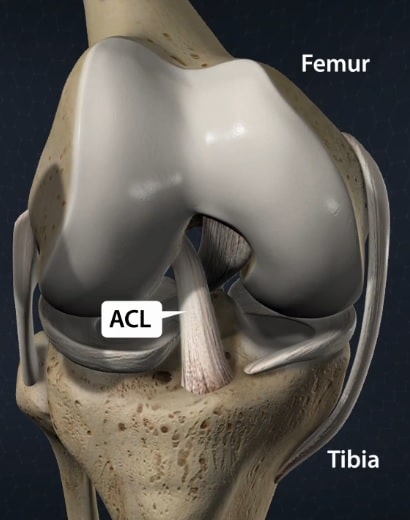

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) attaches from the anterior tibia (shin bone) to the femoral (thigh bone) intercondylar notch. As seen on the diagram, it lies just anterior to (in front of) the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). Both ligaments are named based on their insertion site on the tibia. On the femoral side, it attaches to the posteromedial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. The average length is 33 mm (1.3 inches) and the width is 11 mm ( 0.43 inches). The anatomy and footprint of the ligament are very important in reconstruction.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) attaches from the anterior tibia (shin bone) to the femoral (thigh bone) intercondylar notch. As seen on the diagram, it lies just anterior to (in front of) the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). Both ligaments are named based on their insertion site on the tibia. On the femoral side, it attaches to the posteromedial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. The average length is 33 mm (1.3 inches) and the width is 11 mm ( 0.43 inches). The anatomy and footprint of the ligament are very important in reconstruction.

The primary function of the ACL is to limit anterior translation (forward sliding) of the tibia on the femur in the knee joint. It secondarily aids in limiting the pivot of the knee joint. It has two bundles: an anteromedial (AM) and posterolateral (PL) bundle. The anteromedial bundle is tight in flexion (knee bending) and the posterolateral bundle is tight in extension (knee straightening). Recent evidence has shown that the AM bundle may play a large role in anterior-posterior translation (front to back motion) of the knee, and the PL bundle in rotational stability.

How common are ACL injuries?

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are among the most common sports injuries in America. Close to 200,000 reconstructions are performed annually.

What are some signs and symptoms of an ACL tear?

An ACL injury typically occurs during a twisting injury at the knee. It often occurs in competitive sports, such as from a tackle during football, but it does not always have to include a direct blow to the knee. Sometimes it can occur with a misstep during pivoting.

You may often hear a “pop” and have knee swelling. Most of the time this accompanies a great deal of pain where you may be unable to place weight on the injured leg.

This can be followed by the inability to fully flex (bend) or extend (straighten) the knee.

Some other things that could mimic an ACL injury could be a fracture (broken bone), dislocation, meniscus tear, cartilage injury, or another ligament injury.

If this type of injury occurs to you, you should seek immediate medical attention for appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

How can you diagnose an ACL tear?

ACL tears are often diagnosed based on history and physical exam. During a physical exam, the Lachman or Anterior Drawer test is performed. If your tibia slides anteriorly during these tests more than 1 cm without a solid end-point, then the test is positive and it’s most likely an ACL tear. Other physical exam tests include a knee arthrometer which can measure the side to side difference in the anterior translation of the tibia.

X-rays are not able to diagnose an ACL tear except for a “Segond fracture” which is the avulsion of the anterolateral ligament. This may appear as a fleck of bone on the lateral (outside aspect) of your knee. The anterolateral ligament is an additional injured ligament which often signifies an ACL tear.

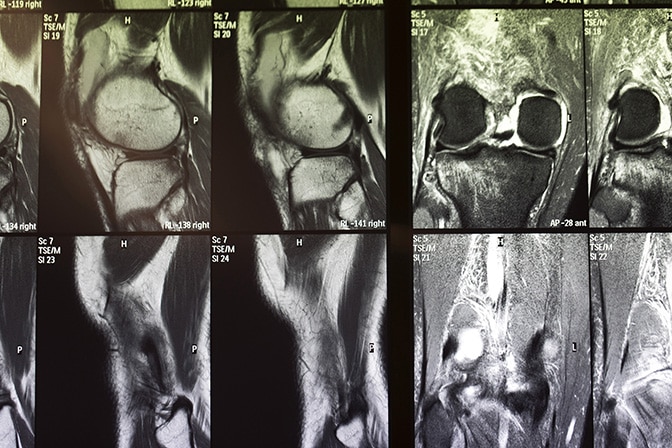

Ultimately, an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) study of your knee can make a definitive diagnosis. This can be very helpful as a surgical plan, as it will also show any other injury that occurred to your knee involving the meniscus, cartilage, or other ligaments. Be sure to disclose to your physician if you have any metal implants, a pacemaker, or any fear of enclosed places, as this can affect your ability to get an MRI.

How do you treat an ACL tear?

Initial treatment should include rest, ice, compression, and elevation. Try to keep it elevated above the level of your heart. Be sure not to put ice directly on your skin, and place it over a protective plastic or cloth. Anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen and naproxen can be initiated if it is safe for you to take these drugs and you do not have any impaired kidney function. Tylenol should be taken as well if your liver function is normal.

An x-ray should be obtained if you are unable to place weight on your knee due to pain. This is to make sure there is no dislocation and no bones are fractured/ broken. Try to immobilize your knee and keep it protected until you seek medical attention.

When you get to your provider, then you will most likely get more information about your injury and the diagnosis. This will help guide you decide whether or not to have surgery for your injury.

When should I have surgery for an ACL tear?

Depending on the degree of the tear, a torn ACL has a very limited healing capacity. In general, a torn ACL is difficult to repair. Though there are special circumstances that can warrant an attempt to repair the ACL, there is a higher rate of failure than traditional reconstruction. The ACL be reconstructed using different tissue from either your own body (autograft) or donor (allograft) tissue.

In general, without a functional ACL, patients should not participate in cutting-sports where side-to-side movements are done with the knee. These sports include but are not limited to soccer, tennis, baseball, basketball, and football. Though the body tries to adapt to ACL deficiency, it is not able to overcome it. (Takeda et al. 2014)* If you are able to safely undergo physical rehabilitation and you do not wish to return to cutting-sports, then you don’t need to have your ACL reconstructed. However, even if you don’t wish to return to cutting sports, and your knee remains unstable, then surgery would be necessary. (Dawson, Hutchison, and Sutherland 2014)*

Some other factors that would require surgery to get better include a torn meniscus, a multiple ligament knee injury, and failure of nonoperative management.

Should I use my own tissue to reconstruct my ACL?

This is an area of heavy research. There are very specific patient and surgeon factors that ultimately will result in the greatest success for athletes. In general, autografts (using your own tissue) have shown to have the highest chance for success without re-tearing the graft in patients under age 35. Although in certain circumstances, an allograft (donor tissue) may be a better choice due to patient factors such as age, bone, and tissue quality. Ultimately, you have to discuss with your surgeon the risks, benefits, and alternatives to graft selection.

What is anatomic ACL reconstruction?

The ACL attaches to the tibia in line with the posterior aspect of the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus. This is an important landmark for surgeons during ACL reconstruction to try to match the native anatomy of the patient. (Hatayama et al. 2013)* The latest evidence suggests that the best outcomes for success are anatomic ACL reconstruction where the patient’s anatomy is restored. (Fu et al. 2014)* (Porter and Shadbolt 2014)*

Bibliography

Dawson, A G, J D Hutchison, and A G Sutherland. 2014. Is Anterior Cruciate Reconstruction Superior to Conservative Treatment? The journal of knee surgery, no. 1 (December 1). doi:10.1055/s-0034-1396017.

Fu, Freddie H, Carola F van Eck, Scott Tashman, James J Irrgang, and Morey S Moreland. 2014. Anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a changing paradigm. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, no. 3 (August 3). doi:10.1007/s00167-014-3209-9.

Hatayama, Kazuhisa, Masanori Terauchi, Kenichi Saito, Hiroshi Higuchi, Shinya Yanagisawa, and Kenji Takagishi. 2013. The importance of tibial tunnel placement in anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association, no. 6 (April 6). doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.02.003.

Luo, T David, Ali Ashraf, Diane L Dahm, Michael J Stuart, and Amy L McIntosh. 2014. Femoral nerve block is associated with persistent strength deficits at 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in pediatric and adolescent patients. The American journal of sports medicine, no. 2 (December 2). doi:10.1177/0363546514559823.

Maestro, Antonio, Miguel A Suárez-Suárez, Luis Rodríguez-López, and Alfonso Villa-Vigil. 2012. Stability evaluation after isolated reconstruction of anteromedial or posterolateral bundle in symptomatic partial tears of anterior cruciate ligament. European journal of orthopaedic surgery & traumatology : orthopedie traumatologie, no. 4 (May 30). doi:10.1007/s00590-012-1018-8.

Mall, Nathan A, Peter N Chalmers, Mario Moric, Miho J Tanaka, Brian J Cole, Bernard R Bach, and George A Paletta. 2014. Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States. The American journal of sports medicine, no. 10 (August 1). doi:10.1177/0363546514542796.

Porter, Mark D, and Bruce Shadbolt. 2014. “Anatomic” single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction reduces both anterior translation and internal rotation during the pivot shift. The American journal of sports medicine, no. 12 (September 19). doi:10.1177/0363546514549938.

Takeda, Kentaro, Takayuki Hasegawa, Yoshimori Kiriyama, Hideo Matsumoto, Toshiro Otani, Yoshiaki Toyama, and Takeo Nagura. 2014. Kinematic motion of the anterior cruciate ligament deficient knee during functionally high and low demanding tasks. Journal of biomechanics, no. 10 (March 27). doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.03.027.

Tiamklang, Thavatchai, Sermsak Sumanont, Thanit Foocharoen, and Malinee Laopaiboon. 2012. Double-bundle versus single-bundle reconstruction for anterior cruciate ligament rupture in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (November 14). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008413.pub2.